Conte Biancamano: A Century of History

For maritime history, 2025 was an important year, marking the centenary of the maiden voyage of Conte Biancamano, the last great transatlantic liner of the Italian Merchant Marine built abroad.

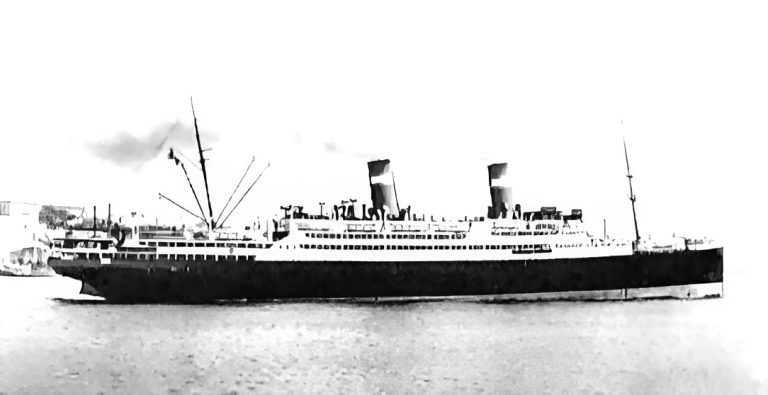

Given the historical period, her name was chosen in honor of Umberto I, known as “Biancamano,” the founder of the House of Savoy. Ordered by the Genoa-based shipping company Lloyd Sabaudo from the Scottish shipyard William Beardmore & Co. of Glasgow—also responsible for building Conte Rosso and Conte Verde—she was launched on April 23, 1925, and delivered on November 7 of the same year. Her maiden voyage departed Genoa for New York on November 20, 1925.

Conte Biancamano

The ship featured a black hull with a straight bow and two iconic funnels painted in Lloyd Sabaudo colors. Her propulsion system, delivering a total of 24,870 horsepower through two double-reduction steam turbines driving twin propellers, allowed a top speed of 20 knots. She could accommodate 1,750 passengers and 459 crew members. Her original gross tonnage was 24,416 tons, with an overall length of 198.4 meters, a beam of 23.2 meters, and a draft of 7.9 meters.

Conte Biancamano was lavishly outfitted and equipped with every modern comfort of the time. Designed to serve both luxury passengers and emigrants, her interiors were conceived by one of Italy’s most renowned architects, Adolfo Coppedè, celebrated for his opulent historicist style.

In 1932, Lloyd Sabaudo, together with Navigazione Generale Italiana and Cosulich STN, was merged into Società Italia – Flotte Riunite, contributing its fleet, including Conte Biancamano, which was assigned to the South American route. Before that, however, she completed six additional voyages on the New York line for the new company, the last of which began on July 1, 1932. By then, the famous Rex and Conte di Savoia were ready to take over the most prestigious and profitable route. From 1934, Conte Biancamano was employed for military purposes, transporting troops and military equipment on behalf of the Ministry of the Navy in preparation for the Ethiopian War. After this assignment, in 1936 she was chartered by Lloyd Triestino and operated on routes to the Middle East. On January 21, 1940, Biancamano was among the ships that rushed to assist the ocean liner Orazio, which had caught fire off Toulon, rescuing 316 survivors. Later in 1940, she returned to Società Italia di Navigazione and was deployed on the Genoa–Valparaíso route via Panama, replacing the motor ship Orazio.

When Italy entered the war, the ship was seized and interned in the Panamanian port of Cristóbal, where she had taken refuge. In December 1941, following the United States’ entry into World War II, she was declared a war prize, converted into a troop transport, and commissioned into the U.S. Navy as USS Hermitage (AP-54). The conversion work was carried out at the Philadelphia shipyards, after which the ship was capable of transporting up to 7,000 troops. The Allies began the invasion of North Africa on November 8, 1942, and Hermitage took part, departing New York on November 2 with 5,600 personnel aboard, who were landed at Casablanca. She returned to the United States on December 11 and was then assigned to the Pacific theater, where she served throughout 1943. After the Normandy landings, she made numerous voyages between Europe and the United States, transporting troops and repatriating wounded soldiers and prisoners, beginning on June 16, 1944. After the end of hostilities, the ship was used to repatriate thousands of American war veterans, first from Europe and later from the Pacific. She was withdrawn from service on August 20, 1946. During her time with the U.S. Navy, she sailed more than 230,000 miles and transported 129,695 soldiers of various nationalities.

Conte Biancamano (3)

After the war, together with Conte Grande, which had suffered the same fate, Conte Biancamano was returned to Italy through a confidential negotiation between Alcide De Gasperi and U.S. President Harry Truman. The agreement stipulated that the United States would formally retain ownership of both vessels for a decade, while Italy would reacquire them through a lease-to-own contract with a symbolic fee of one dollar per year.

The reconversion of the ship into a passenger liner was entrusted to the Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (CRDA) shipyard in Monfalcone. The “Monfalcone chapter” of Conte Biancamano takes us back 77 years, to a time when Italy was struggling to recover from the devastation of World War II. Moreover, Monfalcone itself had been at the center of the tragic events along the eastern border, with its future hanging in the balance between Italy and Yugoslavia for several months. With the 1947 Peace Treaty, Venezia Giulia lost most of its territory, and the town became the last strip of Italian land before the Free Territory of Trieste. In these borderlands, the postwar years were as harsh as the years of conflict. To the destruction caused by bombing were added targeted executions carried out by Tito’s forces and the resulting exodus of more than 300,000 Italians from the provinces of Pola, Fiume, and Zara.

It is within this extremely difficult context that the revival of production at the Monfalcone shipyard must be understood. The CRDA facilities had been heavily damaged by Allied bombing, and at the time Conte Biancamano arrived at the yard, the company was literally divided by the border between Italy and the Free Territory of Trieste, with the Monfalcone plant under Italian administration and those of Trieste and Muggia under Allied control. In such challenging circumstances, the contract for the reconstruction of Conte Biancamano arrived, allowing several hundred workers to be employed in the complex transformation from troopship back into a passenger liner. The highly complex work lasted approximately 19 months—almost as long as building a ship from scratch—and remains the most significant refit carried out at the Monfalcone shipyard in its 117-year history.

It is worth recalling that Biancamano was triumphantly welcomed back in Genoa following her return to Italy on August 25, 1947, and was subsequently laid up in Messina before arriving at Monfalcone on March 28, 1948. The task facing the Monfalcone workforce and technicians was immense: they had to restore a hull that had served as a troop transport and had lost all of its prewar luxury fittings to its original role as a passenger liner.

A study model of Biancamano in her military configuration (summer 1948) was created by skilled carpenter-model makers. This model featured a very original characteristic: an interchangeable bow. In fact, modifications to the ship’s extremity were being studied both to improve her nautical performance and for aesthetic purposes. Two designs for a new bow were created and mounted on the model; once the final design was chosen, work proceeded. This operation was carried out with the ship afloat, and to facilitate the process, the bow was raised as much as possible by ballasting the stern. Upon completion, the ship’s overall length measured 202.7 meters, compared to 198.4 meters of the original Scottish version. Other works significantly altered the ship’s silhouette, notably the reshaping of the funnels. At the same time, the interiors were restored, featuring a “pluralist” post-war design approach, with lounges designed by various artists and architects. Signatures included Triestine architects Romano Boico, Aldo Cervi, Vittorio Frandoli, and Umberto Nordio, as well as Gio Ponti, Gustavo Pulitzer, and Nino Zoncada. On board, works by some of the greatest artists of the era were installed, including Marcello Mascherini, Zoran Music, Mario Sironi, Dino Predonzani, Massimo Campigli, Ugo Carà, and Salvatore Fiume, among others.

Conte_Biancamano_a_Napoli

While this floating palace took shape internally, technological modernization of the ship continued, including the installation of a new enclosed bridge and new cranes for lowering the lifeboats. In August, the first motorized lifeboats were completed by the shipyard’s boat workshop, so that Biancamano would be ready to cast off for sea trials and the subsequent dry-dock in Venice. The ship left her berth on September 8, 1949, sporting her new white livery and funnels painted in the colors of Società Italia. Everything was ready to test all onboard systems and rigorously assess the nautical capabilities of the reborn ocean liner. Once the trials were completed and she returned to the shipyard, the finishing touches on the exterior spaces were completed, and the remaining lifeboats were installed.

The day of farewell to Monfalcone came on October 21, 1949: once at sea, further machinery tests were conducted before arriving at the Maritime Station of Trieste, where a celebration was organized for her second inauguration. Her “Giulian” days were now over, and on October 26 she departed Trieste definitively, heading to Genoa, her home port, from where she would resume commercial service. The white livery clearly indicated her assignment to the South America line, although in her new life with Società Italia she also undertook trips to North America, such as replacing the sunken Andrea Doria in 1956.

In 1960, after 364 line crossings during which she had carried 353,836 passengers, she was decommissioned, stricken from the register, and sent for scrapping, which took place in La Spezia the following year. During this process, however, a small portion of the ship was saved and later reassembled at the Leonardo da Vinci National Museum of Science and Technology, where it is still on display today.

Don’t miss news, updates, and reviews from the world of cruising on Cruising Journal, with photos, videos, and cruise offers.